|

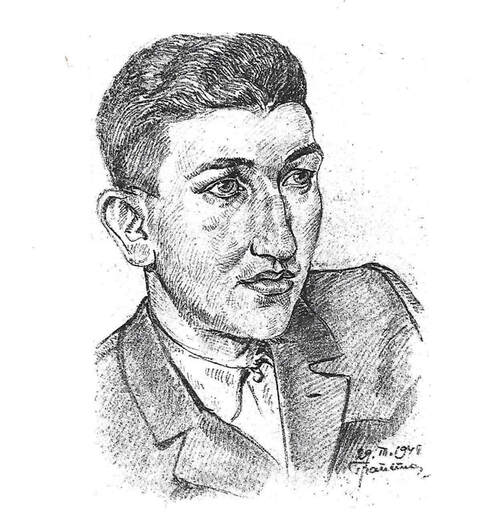

John was sketched by an artist* in 1948. My uncle John Boleak (1925-2008) was a charming man who made everyone laugh. He also survived five years of captivity in Russia. Contents:

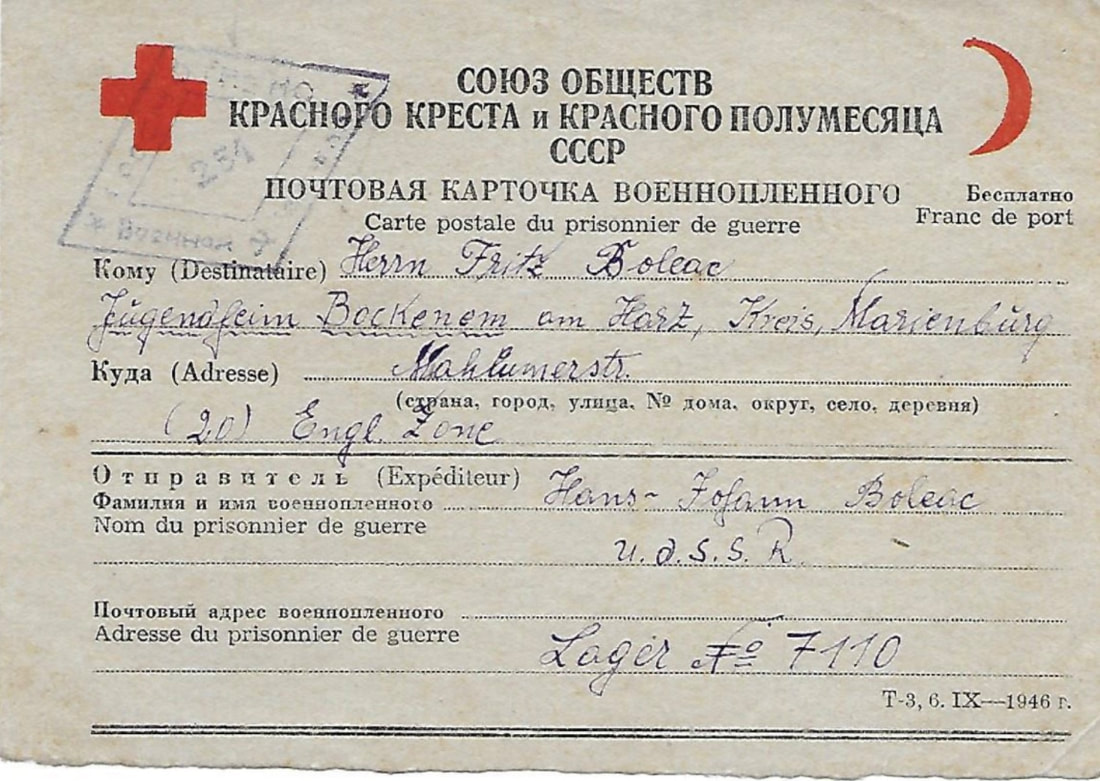

Introduction: Gulags and other employment

John served in the Luftwaffe in World War 2, and was shot down in Austria. John’s daughter Anne recently shared some new details with me. John flew in 52 missions over Africa. After being shot down in Austria, he was treated for malaria in hospital. When he recovered, John was told that he was headed home, which was then Jena, Germany. But instead of seeing his family again, he was sent to a Russian Gulag. Confining people in Gulags was the regime’s way of getting slave labour, in a show of force that was often deadly. This fate happened to countless innocent people who were falsely accused of crimes against the state. After the war, it was also the fate of many in East Germany, then under Russian control. Those found to be born in Russia were told that they were being sent home, but the destination was a Gulag. (My uncle Jakob Plett talks about this experience in his story, Life in a Gulag.) Being sent to a Gulag could also happen randomly, which happened to my father in 1947. He wanted to see my mother and their new baby Rudy for the first time in Jena. After the Russian border guards denied him entry from the west at Helmstedt, the English authorities gave him fresh papers and a ticket for a military train. “The Russians are not allowed to stop that train according to the Yalta agreement,” they told him. That was the post-war pact that gave East Germany to the Russians. But that didn’t stop the Russian guards with machine guns at the first station in East Germany. They took out my father and some others, loading them all on another train packed with young men with standing room only. My dad knew that this train was headed to Russia for slave labour. When he started to try to open a window, two other men joined him in jumping out the window from the moving train. My father shares how grateful he was for his escape in a video, “I escaped from a train.” John was a fit young man, a good candidate for slave labour, and perhaps that was enough to seal his fate. He was imprisoned for nearly five years, from about 1945 to December 1949. When the war was long over, he was still considered a prisoner of war. The Red Cross helped prisoners of war in Russia to send postcards to their family. One of John’s postcards is below, preserved by his brother Isaak and Isaak’s daughter Esther. John’s skill as a mechanic became very useful in the Gulag and helped him to survive. He learned how to maintain and repair aircraft and vehicle engines when serving in the Luftwaffe. In the camp, he took broken parts and managed to piece together a functional vehicle. Then he became the driver. A fourteen-year-old guard pointed a gun at him while he drove. John could have overpowered the youth, but where could he run to? In Siberia, there was nowhere to go. It was a prison without walls. He had to go into the forest and load up lumber, then he was told where to deliver it. Privileged party members needed lumber for their personal homes. Once he even drove to the Crimean Peninsula. The guard fell asleep along the way, but escape was not an option. Rations in the Gulag were never enough, but the kindness of strangers helped John to survive. When he stopped in a village or city, women who had lost men in their own families, felt sorry for the starving young man, and gave him bread or other scraps of food. My father tells the amazing story of how John was finally released in the video below. John and my father, Peter Plett, were actually cousins, whose mothers were sisters. They met again in Canada, and helped each other with their challenging start in a new land. In the early 1950s, John, my father and their cousin Henry Graewe, worked together hauling coal in Vancouver. The coal was used to heat local homes and stoves. My father also tells that story below. After John sponsored his brother Isaak, the trio of cousins in Canada became a quartet. John often cracked jokes. At my mother’s funeral reception, he was sitting at the next table, and said to those around him, “I used to be young and beautiful. Now I’m only beautiful.” At that difficult time, he made us laugh again. My father was very close to his cousin John, and was thrilled to be present when John finally made a commitment to Christ, not long before he passed. If you met him, you would not soon forget him. I hope you enjoy this encounter with my uncle John. Postcard from a Gulag: Home for Christmas Front of postcard from John The Red Cross facilitated communication from prisoners of war. John wrote this postcard to his brother Isaak, then called Fritz, from camp No. 7110. Another card was written from camp No. 7232; locations are unknown. The original text is in the German language version of this blog post. Front of card: Postcard of prisoner of war — Free of charge Recipient: Mr. Fritz Boleac Youth hostel, Bockenem am Harz, Marienburg district Address: Mahlumer Street (20) English Zone [part of Germany under British authority after the war] Sender: Name of prisoner of war: Hans-Johann Boleac, USSR Address of prisoner of war: Camp No. 7110 Back of card: 10 Nov. 1948 My dear brother of my heart, Your sudden silence is unexpected, but not inexplicable to me, because you think I’m already on my way home. Dear brother, as long as you receive postcards, answer them calmly, because when I travel home the cards will get lost, which isn’t that bad. The main thing is that I will be with you for Christmas. Dear Fritz, I can hardly imagine the joy when we will be together on this biggest holiday, it will be the most beautiful and best gift of my life. Now dear brother, a thousand greetings in advance to all acquaintances and relatives. When you write to Jena, greet everyone very warmly. Is Alex already home? We’ve been apart for two months now. We’ll meet again at New Year’s. Now dear Fritz, a warm greeting from your brother Hans. Isaak notes: Replied right away on Nov. 29 about Alex [Kirlik, a recently released prisoner who happened to have a sister, Maria, whom John later married.] How John escaped a Gulag Video transcript: Irene: Did John ever tell you about when he was a Russian prisoner of war? Peter: Oh yes, he told me a lot about the Russian prisoner of war, somebody— he was five years already in the prisoner camp, and as I said before, he was driving a truck there, delivering lumber for the bosses, to their homes, their summer homes, and all kinds of places, to those people that run the prisoners. They had some privileges, that they could use some lumber from the city, from the country. But somebody reported him, that he said something that was not right, that was against the teachings of communism, and so he was called into the office. He told me, and then the commandant— chief prosecutor there said to him, “I hear that you say that all the people that are against us have to be eliminated.” And Boleak said to him, “I did not say that. Lenin said that in his book, that you gave me.” They gave each prisoner a book about communism teaching how to become a communist and how to work as a communist. And he went to a page where Lenin said this, all the enemies of the communist state should be eliminated. And they were so impressed with his knowledge of this book from, was, in Lenin’s name presented, that the prosecutor said to him, “He can go with the next train to his homeland, Germany.” That’s how John Boleak was actually released from prisoner camp in Russia, that’s what he told me. So that was amazing. Then he went to Jena, where he used to live, and he got in touch with other people and that’s where he met his wife, and they married I think in Gronau-Westfalen, from where they went to Canada. Hauling Coal in 1950s Vancouver Video transcript: Peter: John Boleak was in Russia in prison, a war prisoner, and he was driving a truck out there, he learned to drive the truck, and so he was very handy with driving and he worked for a company, a coal mining company in Vancouver. Most people in Vancouver were having their furnace and stoves heated with coal from Alberta. It was imported here, and he worked for the coal company, Ami Coal Company, and actually he got me a job there too, and I was sacking coal and each coal wagon, there were 40 tons of coal. And between Henry Graewe and me, the two of them, we sacked 40 tons of coal in one day, each 20 tons. That was a very very hard job, and we weighed it, put it in sacks, weighed it, and piled it. Then John would come and move it away with the truck. So we worked together, the three of us. At the time we started to work in that coal company was when all three of us lived in Abbotsford, and we took the bus into Vancouver, and we rented a room from a Mr. Langemann on 43rd Avenue and Fraser Street, close to Fraser. We rented a top room and that’s where we cooked and slept and everything. We couldn’t afford much more and that’s where we stayed. Mr. Langemann was one of the ministers in the M.B. Church at that time, who owned that building. Irene: Do you know which M.B. Church? Peter: Yeah, that’s the First Mennonite Brethren Church in Vancouver. Irene: Vancouver M.B.? Peter: It was on 43rd and Sophia [Street]. And it’s still there. Every weekend we would go to Abbotsford and come back with the bus to Vancouver. All week we were in Vancouver, working, yeah. Irene: So the women were on their own. Peter: The women were at home, looking after their kids (chuckles). I was cooking, I could cook, and Henry was good at cleaning up, so he cleaned up, and John was eating (chuckles). He enjoyed the food. Irene: And he organized your work, so you figured that was enough? He got you the job? Peter: Yeah. No, I enjoyed serving my cousins (chuckles). Irene: What did you cook? Peter: Oh, a lot of things, I learned to cook a lot. Perogies, I made, a Russian thing, food. Irene: Delicious! Peter: And I cooked borscht, oh and all kinds of other soups, spaghetti, meatballs, oh yeah, I made all that. Irene: Sounds tasty. Peter: After work. Irene: After work, wow! That’s great. Peter: And we never were out of touch (chuckles). We always kept in touch and visited and shared our lives together. John Boleak and Maria Kirlik 25 June 1950, Gronau-Westfalen, Germany Obituary John was born the first of nine** children in Friedensfeld, Ukraine on March 29, 1925 to Dimitru and Agatha Boleacu. The family later immigrated to Romania where he met Maria Kirlik. They were married in Germany on June 25, 1950. In the same year the newlyweds made their way across the Atlantic to Canada to start a new life. Their first stop was Swift Current, Saskatchewan. It was here that their first son Deattar was born. After a short stopover in Yarrow, B.C., the family made their way to Vancouver, where the rest of their children were born. [The house on] Chester Street became the family home, and has been for the past 50 years. It was in this community that many lifelong friendships were made. Four years ago, John was diagnosed with Alzheimer's Disease. In May 2007, he was admitted to a full care facility. On Friday, August 9, 2008, John was admitted to Vancouver General Hospital and passed away peacefully in the early hours of August 13, 2008. John is survived by his beloved wife Maria of 58 years, his children: Deattar (Madeline); Ruth (Gary); Anne, John, Ed (Donna); Leonard (Sandra). His grandchildren: Stephanie (Steve); Amy (Richard); Emily, Jocelynn, Robert (Carrie); Steven (Lisa); Dan, Catherine, Michael, Brennan (Dale); Spencer, Lenay, Jonathan, Alexis, Victoria and Shaylyn. His great grandchildren: Geordie, Zoe, Brooke and Nolan. Also survived by his brother Willy (Anna) and sister Liselotte of Germany, his brothers Daniel and Peter of Romania as well as his special cousin Peter Plett with whom he spent countless hours with during the past years. John was predeceased by his parents, three sisters and one brother, and most recently his cousin Henry Graewe. We will miss you dearly Dad, but you are now released from your pain. Until we meet again. * I have not been able to identify the artist of the sketch of John, who signed their work. It was likely another prisoner of war in the Gulag. If the artist or their surviving family contacts me, I would like to credit him or her. **We later learned that John’s parents had 11 children, from Isaak’s story. P.S. John’s wife Maria died in 2017; son Deattar in 2009; daughter Ruth Frick recently on Oct 26, 2020. Ruth was very interested in family history, and this blog post is dedicated to her memory. John and Maria with son Deattar, 1951, Swift Current, Sask. John & Maria with children Ruth, Anne, John, Ed and Dieter (left to right), 1958, Vancouver, B.C. Daughter Ruth Boleak, 1969, and her marriage to Gary Frick

7 Comments

Marita Wallace

3/23/2021 07:00:11 pm

Thank you for sharing this. He was my Uncle as well. He was married to my Aunt Marie. My Dad was Paul Kirlik.

Reply

3/25/2021 11:46:52 am

That's wonderful! Thanks for sharing that. I heard that the Boleac family didn't feel so alone after their immigration, with the Kirliks nearby.

Reply

Ingrid Le Beau (Boleac)

3/26/2021 08:20:15 pm

Irene, so appreciate all the commitment and research you’ve done. Family history is so important. I haven’t had much time for ours due to work, health, now babysitting. Also been sorting my husband’s family photo albums and sharing with his cousins etc, very arduous and time consuming. I have given Esther some info she didn’t have before. I also have Dad’s (Isaak aka Fritz) Ww2 tin from his belt that was used for shaving, drinking and eating. He was nicknamed Fritz because Isaak is a biblical name and Hitler would think he was a Jew.

Reply

3/27/2021 04:30:37 pm

Hi Ingrid, thanks for your comments, nice to hear from you! Family history can be a tangled web... What an interesting artifact you have! It was sad how beautiful biblical names were taken away because of senseless discrimination. But there were also many stories of survival and enduring love.

Reply

Kathryn Boleak

6/9/2021 02:20:47 pm

I appreciate the time that went into this. There was a lot I didn’t know about my grandfather. Very well written. Thank you.

Reply

Harry Patrick

5/10/2024 06:24:57 pm

Fascinating . I knew John from a very early age. He worked for my father driving trucks hauling hog fuel and various lumber mill by products and coal too . The company was Allied Heat And Fuel located in Vancouver. He used to sit me on his lap and let me hold the wheel and ,steer the truck ( old International , no power steering! Guess who was really in control ! John was like family, could fix and do anything , always positive and cheerful . He told me that he was in the German Air Force and shot down or crashed but never elaborated or let on the suffering he must have endured . He was a great man and good friend . Wish I had known more about his personal life . Cheers Harry Patrick

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

WriterIrene Plett is a writer, poet and animal lover living in South Surrey, British Columbia, Canada. Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed